Remains of St. Calixtus in St. George's Chapel

From early Christian

times, the bodily remains of the Saints were highly respected as

they were considered proof of the existence of a person blessed and

chosen by God. Worship of the remains enabled believers to

experience what they felt to be in physical contact with holiness.

In the Middle Ages and during the Baroque period, the bodies of the

Saints were displayed in decorated cabinets in churches and chapels

for people to worship.

From early Christian

times, the bodily remains of the Saints were highly respected as

they were considered proof of the existence of a person blessed and

chosen by God. Worship of the remains enabled believers to

experience what they felt to be in physical contact with holiness.

In the Middle Ages and during the Baroque period, the bodies of the

Saints were displayed in decorated cabinets in churches and chapels

for people to worship.

There are precious remains, first mentioned in 1334, in the Castle Chapel at Český Krumlov. From the 14th century, valuable relics were also worshipped here. They were displayed once a year on Corpus Christi day, during the festival when these Holy Relics were displayed. The Emperor Charles IV began the tradition of such festivals and the Rosenbergs continued it in Český Krumlov. In 1410 the remains of St. Jiljí and St. Calixtus were borrowed from the Augustinian convent in Třeboň for one of these festivals on a long-term basis.

They were probably the remains of Saint Pope Calixtus I who died around 222 in Rome. Even though he died a natural death, he was considered a martyr because of the suffering he had to endure and which shortened his life. In the 9th century the remains of St. Calixtus were disposed between several Roman churches in Naples and France. Subsequently, the Emperor Charles IV, a famous European collector of relics, obtained a portion of the head and probably gave it to the Rosenbergs. The remains of St. Calixtus were kept in the chapel in a head-shaped casket until the year 1614, when they were taken away. We have no information about them after that time.

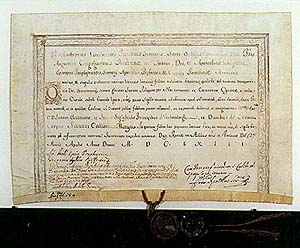

After a couple of decades, relics of a saint with the same name appear in the Český Krumlov Chapel. The Pope Alexander VII gave them to Duke Johann Christian I. von Eggenberg in 1663. Bishop Ambros Landucci brought the Saint\'s skeleton and a container with his blood from Kyrenaika (today\'s Libya), and wrote a document authenticating them. It is therefore evident that these are not the remains of Pope Calixtus I, but of some other unknown martyr from North Africa, which was then a part of the Roman Empire. In the Baroque period, many remains of little known saints were brought to Bohemia by the aristocrats and clergy dignitaries returning from their journeys. T\'he respect shown for these relics, quite bizarre and incomprehensible to us today, became one of the typical signs of the extreme religious fervour of the Baroque period.

In 1678 the Prague

Archbishop Bedřich z Valdštejna confirmed the authenticity of the

skeleton and the blood of St. Calixtus, because without the

approval of the local bishop, the relics could not be publicly

worshipped in the Chapel. During the costly reconstruction of the

Chapel in the 1750\'s, a glass cabinet was placed above the

tabernacle on the main altar. This cabinet, lined with red velvet,

contained the remains of the Saint, richly decorated with gold,

along with the vessel containing his blood. It indicated the fact

that Calixtus was a martyr because he shed blood for his religion.

That is why such great attention was paid to it. Alongside the

relics, there was also a document confirming their

authenticity.

In 1678 the Prague

Archbishop Bedřich z Valdštejna confirmed the authenticity of the

skeleton and the blood of St. Calixtus, because without the

approval of the local bishop, the relics could not be publicly

worshipped in the Chapel. During the costly reconstruction of the

Chapel in the 1750\'s, a glass cabinet was placed above the

tabernacle on the main altar. This cabinet, lined with red velvet,

contained the remains of the Saint, richly decorated with gold,

along with the vessel containing his blood. It indicated the fact

that Calixtus was a martyr because he shed blood for his religion.

That is why such great attention was paid to it. Alongside the

relics, there was also a document confirming their

authenticity.

In Český Krumlov, as a result of a strange coincidence, the remains of two different saints with the same name were worshipped. One, a Roman Pope, and the other, an unknown martyr from North Africa.

(zp)